American Music Education Was Not Born Here

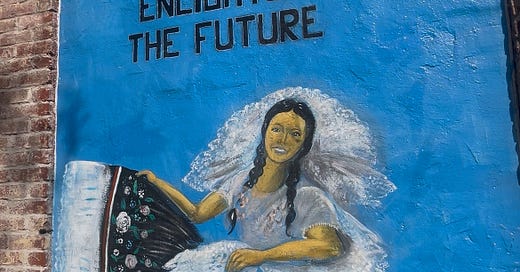

Photo taken by me on Olvera Street, Los Angeles. Olvera Street is known as the birthplace of Los Angeles.

Let’s start with a little definition.

Immigrant (noun): a person who comes to a country to take up permanent residence. From the Latin migrare — “to move from one place to another” (Merriam-Webster, n.d.).

I prefer to call myself a second-generation immigrant, meaning I was born and raised here in the United States, and both of my parents were born and raised in the provinces of the Philippines. I am (but was not always) proud to include “immigrant” as one of my identity markers. As I have gotten older, I have realized there is something uniquely powerful about growing up with that bicultural experience, constantly navigating what it meant to be both Filipina and American.

As a child, it was ingrained in me to be “as American as possible”: speak, read, and write in English, and act like an American, whatever that meant. It meant putting aside my “Filipino-ness” aside in spaces where I may be looked down upon for it. In truth, I was being pushed to assimilate. But in some immigrant mindsets, assimilation often meant survival. Because to them, America is the land of prosperity and opportunity. Woohoo.

Recently, I began coursework for a Doctor of Arts in Music Education, and one of the required classes is called History of Music Education, focused on the development of music education in the United States. Before the course began, I found myself wondering: How often will we address and acknowledge the importance of Indigenous music in the story of American music education?

(I am also at the point in the course where much of the text and discussions are focused on giving credit to only White men in the early developments of music education in the United States but…that’s another topic for another day.)

Even after just the first few weeks, it dawned on me that “American” music education didn’t just appear out of thin air.

It began with immigrants.

Do a quick Google search on “History of Music Education in America” and you’ll likely see singing schools listed as the earliest documented events. Lowell Mason is often called the “Father of American Music Education” (Mark, 2008). But what many of these articles fail to explore is the why behind the singing schools.

Before formalized music education existed, church ministers noticed a need for more in-tune singing during services. This then prompted the rise of music training in schools (Britton, 1958). But let’s go back even further. These ministers belonged to the Puritans and Pilgrims, two separate groups from the Protestant Reformation who left England in search of religious freedom and a new beginning.

Settling in a new land wasn’t easy for them. Although music held religious importance for the Puritans and Pilgrims, their immediate focus was on surviving and adapting to life in an unfamiliar place. This also meant attending to basic needs before anything else, including music proficiency in their people.

Of course, we also have to acknowledge that these people were colonizers. They arrived with a sense of entitlement to this land, despite the fact that Indigenous people were already living here. (I could go on about colonization, but that’s not my main point here.)

Let me bring us back to the definition of an immigrant:

Immigrant (noun): a person who comes to a country to take up permanent residence. From the Latin migrare — “to move from one place to another” (Merriam-Webster, n.d.).

By definition, the Puritans and Pilgrims, who established the foundation for singing schools, were, quite simply… immigrants.

And yet over time, especially in recent years, the word “immigrant” has lost its original neutrality and instead become racialized—a label more often imposed on people of color rather than white Europeans (Chavez, 2008). How sad it is that we forget this country was literally built by immigrants, the very people who fled their homelands in search of a better life.

Historical accounts love to credit singing schools as the roots of music education in America. But I would argue differently.

By definition, it all started with immigrants.

References:

Britton, A. P. (1958). Music in early American public education: A historical critique. In N. B. Henry (Ed.), Basic concepts in music education (pp. 21–49). University of Chicago Press.

Chavez, L. R. (2008). The Latino Threat: Constructing Immigrants, Citizens, and the Nation. Stanford University Press.

Mark, M. L. (2008). A Concise History of American Music Education. R&L Education.

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Immigrant. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/immigrant

Some Things to Share:

I contributed a chapter to a new book that is fresh off the press this month - Needs Before Notes! This chapter is a slight adaptation of the introduction I wrote for Portraits of Music Education and Social Emotional Learning (aka the purple book), but I felt these perspectives were essential to include in this new context. You can purchase the book here.

I am keeping my summer low-key yet somewhat occupied. I am taking two grad classes myself (one on history of American music education as mentioned earlier and another on how to be an administrator in a musical context - so much good stuff!), teaching one through VanderCook’s MECA program, and trying to work slowly on…a potential book? Maybe. It’s all a learning process, and I am mentioning it here to keep myself accountable.